Author: Benjamin Coovi DAKO, PhD

Doctor in Political Science, Public Policy Analyst

Expert in Health, Professor of Health Policy at the National School of Administration and the

and the Doctoral School of Legal, Political and Administrative Sciences from the University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin.

The Republic of Benin has known since its independence in 1960, several generations of health policies. As a former French colony, the country has experienced the health strategies modeled on current practices in the metropolis. Most of the said strategies relate to the control of tropical infections and very few were oriented towards prevention. It was only after the World Health Conference held in Alma Ata in 1978 that on primary health care (PHC), that Benin has begun its march towards strategies clean sanitary facilities, which more or less take into account the health determinants of the country and public health priorities. In this article, we will discuss, in part (A), of the process and influences that characterize the first health policies, that is to say the influences of colonial heritage and endogenous practices; part (B) will be dedicated to difficulties in health planning in accordance with international standards since the 1980s, and, finally, part (C) will be devoted to the perspectives that emerge from the courageous reforms initiated since 2016 by the “Rupture” regime of President Patrice TALON.

A- Health policies in Benin: post-colonial heritage and influences of endogenous practices

According to Vincent Lemieux1, “Public policies, whether in the health sector or in another sector, can be defined as attempts to regulate situations presenting a public problem, in a community or between communities”. Based on this author, we can define health policy (or health policy, or even public health policy), as all the strategic choices made by public authorities to improve the state of health of the populations for which they are responsible. . This is in particular of :

✓ determine the areas and fields of intervention;

✓ specify the objectives to be achieved, as well as the judicious choices in terms of priorities for the populations and

✓ define strategies and actions, and plan the means to be mobilized to achieve them.

Health policies correspond to the English term “health policy” which brings together health plans, strategies and programs in this sector. Just as the systems of are not limited to health care systems, so it would be wrong to limit the health policies to health care policies. Furthermore, a public health policy presupposes a set of strategic choices made by the public authorities, in collaboration with the private sector and other non-state actors, to define their scopes of intervention, the general objectives to be achieved as well as the means which, to this end, will be implemented. As recognized by Raymond Massé2 who considers that public health is a public policy to determine “The nature, scope, financing and management disease prevention and health promotion interventions. “. Taken under this angle, public health policies correspond to the English term Policy, and this is precisely here, for the public authorities, to create the necessary favorable conditions for improve the health status of populations.

The literature review carried out with a view to bringing together the constituent elements of the history of public action in health in Benin revealed the lack of enthusiasm of researchers on this subject. Our research on the subject has indeed proven that the few works or theses having addressed the subject have dealt with it very partially, mainly omitting the history of the policies applied to the protection of healthy people, except for the thesis defended by Fidèle Kadoukpè AYENA3 who partially mentioned it.

Indeed, Fidèle Kadoukpè AYENA, by studying global security in the light of public health in Benin, forged a linear description of public action, from colonization until after the country’s independence in 1960. In his thesis, the author highlighted the intrinsic link between the health and social policy specially designed and implementation for African natives by the colonial administration. It continues its development through the public health action adopted and led by the post-colonial health authorities, the difficulties of governance of the sector, the adequacy of the technical platform as well as the lack of effective participation of the many actors who must be involved.

From the analysis of health policies in general in sub-Saharan Africa, it emerges that the organization and management of collective hygiene by public authorities goes back during the colonial era. The colonial power was, so to speak, at the origin of the introduction of a preventive and pasteurian medicine against tropical endemics – infectious or not – including the many nosographies drawn up by the colonial Administration made it possible to control, to control or even eradicate certain nosological pathologies in hot countries.

With independence, these public health programs were logically transferred to the new States which, in fact, have pursued the same admittedly insufficient efforts to rationalize and institutionalization for public and biomedical management of the problems sanitary. As a result, some traditional medicine practices – therapists – healers, fetish-therapists, ancestral traditions, were more or less relegated as obsolete vestiges of ancient peoples for the benefit of an emerging medical modernity whose birth was concomitant with the very appearance of the State in Africa.

However, this relegation of ancestral customs and certain ways of life by the authorities public, has not always received the support of the beneficiary populations. Witness the numerous popular resistances to the policies of community sanitization and direction framework of the living environment put in place by the State. Thus, in Benin, under the regime Marxist-Leninist of Mathieu Kérékou4, the innumerable irruptions in the markets and squares public, nurses flanked by law enforcement officers with their repressive device, have quick to nourish in every respect the fears and aversions of the merchants and the people in his together, with regard to a State considered brutal and dictatorial with regard to traditions and customs ancestral. These local practices, including religious rites, being considered as potentially retrograde by the revolutionary power of Kérékou. Thus, as Emmanuelle Kadya Tall5 reminds us, in 1976, an ordinance established an antifeudal law and anti-witchcraft whose objectives are as follows: “The undermining of the economic base of feudalism ; the undermining of the ideological foundations of feudalism; the undermining of feudal culture; the fight against witchcraft. “.

Nevertheless, these policies of control of social order and public health did not give the long-awaited results and were to some extent counter-productive. The different awareness campaigns are in fact badly perceived by the populations associating for example urban sanitation programs, the fight against erosion and the excavation of roads vehicles, or even vaccination, a political subterfuge always to better control and oppress them. Thus the health and hospital model did not have from the outset convinced the African populations in general and those of Benin in particular, as well observed Wim Van Lerberghe and Vincent de Brouwere6 who affirm that the care in Africa, as soon as they are transposed, “are associated with an institution and not with the image of the individual caregiver and, what is more, to an institution that is associated with power. It’s true especially for the hospital, the symbol par excellence of the “sorcerer’s state”, but also for the missionary or private clinics. Environmental health activities of administrations cities are even further removed from people’s daily lives and quite perceived as linked to military and/or administrative power.

Despite these failures – aggravated by a rather gloomy economic context – the succession is assured by international institutions such as the WHO, goes in the direction of a permanent research effectiveness in managing public health issues in the political arena of state power. Thus, the promotion of primary health care (PHC), stemming from the Alma-Ata Conference of 1978 is proof of WHO’s political will to strengthen the role played by the State in the organization of health care by encouraging more popular or community participation.

This change in the delivery of health care through the ruralization of PHC militates de facto for the institutionalization of public health by promoting understanding of the populations benefiting from public health services. But the ineffectiveness of the PHC had led the States, including Benin, in 1987, under the banner of the WHO, to the adoption of the Initiative of Bamako, relating to the local self-financing of health care, to its being free for the mother, the child and the most vulnerable, to the supply of self-sufficient essential drugs maintained by a certain participation of the populations concerned. Thus, to take up the assertions of Wim Van Lerberghe and Vincent de Brouwere, “That would solve the problem recurring costs and that of the underutilization of services, while avoiding the damage of a wild privatization. “.

Even today, and in every country, public health – if only through public hygiene – is required everywhere, from the bleachers of public education services national and territorial administration to the forecourts of the various sectoral ministries. In other words, the entire public space of the administrative and political apparatus of the State is now governed by public health standards or rules. But the state, the institutional apparatus of public power, is not only this public space for the administration and monitoring of collective interests. It is also and above all its political space, which cannot exclude a certain progressive politicization of this general interest represented by public health.

Patrick Hassenteufeul7, for his part, while emphasizing the interaction between the actors collective, individual and even interdependent, in his analysis of the “networks of action action”, highlights that: “Public action is no longer conceived as a linear linking of sequences but as the product of multiple interactions between various actors”. In other words, the development, like the implementation of public action healthcare, is no longer dependent solely on state or sub-state actors in the sector, but on a whole tangle of civil, economic, public and private health operators. This is in this context of reticular games and this configuration of multiple actors that the public health programs – health public action among public policies – are defined and coordinated by public authorities. Public health action is therefore the result of a social, transparent and democratic consensus. Health issues public and their planning then fall within the literature of political science, of the action government public. Then, as we can see with these different authors, it is through research in public action that political science is more interested in the study of collective risks as well as their probable disadvantages. for human health and for the natural environment.

Benin has had difficulty, for decades, in mastering the offers of care in a vision of population health security. This is not only due to often bad strategies formulated at the political level, but also to the proliferation of actors providing therapeutic care services. On the one hand, we see the public hospital sector with a monopolistic actor – the State, its hospitals or care units suffering from a lack structure of medical-technical equipment. On the other side, a private sector with a myriad actors including, among others, private clinics more or less equipped than the public health facilities. This private sector is also more resource-rich human than medical and are therefore perceived as more effective and valued by populations, at least, by those of them capable of adapting to a practice relatively exorbitant price. Far from it, for the small clinics, the most numerous, led by nursing staff who are often poorly qualified in this medical care market. In an analysis made in his thesis, Fidel K. AYENA8 observes that, “…apart from these representatives from the biomedicine sector, the care market and public health also brings together supporters of traditional medicine: herbalists, traditional healers, healers falling either under the magico-therapeutic model, or simply claiming the legacy of ancestral therapeutic knowledge”. To these actors or professionals of care, we can add certain faith groups including Christians, Muslims and different sects with sometimes syncretic therapeutic methods, that is to say, a process of healing that combines the power of Jesus Christ, practices of herbal medicine or rituals close to black magic. The syncretic nature of these new denominational practices is highlighted by Joseph Tonda and Marc-Éic Gruénais9 who think that: “…one of the explicit functions of these movements, which mix more or less Christian elements and elements of the traditional religious worlds, is to cure all the ills from which the Africans”.

Today, it is clear that monotheistic religious movements, which reject any link with the tradition, are successful with the unbelieving populations in particular, especially those in rural and peri-urban areas. Their self-proclaimed primary mission is miraculous healing, mostly through prayer, laying on of hands, and water. blessed. They offer a satisfactory compromise for these populations between the remedies that fall of biomedicine and traditional healers and other divine healers. Contrary to first, these religious movements gave meaning to illness by referring it to a universe where the individual must confront and protect himself from the forces of evil, explanatory, in the last instance, of misfortunes that overwhelm him. Unlike the latter, these movements depart from the traditional world and relics of the past to which traditional healers and diviner-healers are still attached.

All in all, the day after its independence10, the Beninese State experienced difficulties in set up an adequate health organization. There was indeed a lack of health strategies as part of a clear vision of prevention and therapeutic management of diseases. Also, the multitude of actors in the health system, composed of both biomedicine professionals and traditional healers working in a clear-cut compartmentalization, constitutes another major challenge to which adequate solutions remain to be found. These difficulties mentioned are, among others, among those which push populations into a profound disarray in the sometimes unlimited quest for better care in the event of illness.

B- Chronic planning difficulties

In some health planning documents and evaluation of the implementation of policies identified on the spot, the emphasis is barely placed on the development processes that require, according to international standards, that the principles of intersectorality and health democracy, involving all actors, including field agents and even consumers. Also, the field surveys carried out as part of the drafting of the this article have they been interested in deepening knowledge about the planning process against the background of the concept of protection of persons in health. We will see here, respectively, how the noble aspirations of the “State providence” of Benin to establish adequate health policies have tipped, despite themselves, to the metaphorical “sorcerer’s state” and the incremental nature of the various health policies who have succeeded each other since the 1980s in the country.

b.1 The shift between the aspirations of the welfare state and the resignation of a “sorcerer state”.

Substantial scientific work has been carried out by eminent researchers, nationally and internationally, on the providential aspirations of African States to provide a public service. of adequate health to the populations and the harsh economic realities that these States face. Benin is one of the latter.

The economic realities against the background of the persistent situation that Benin has experienced are the consequences of wandering in terms of its governance for decades and the difficulties international economic conditions, which do not always make it easy to accomplish the Republican public health mission.

Bernard Hours, in his socio-anthropological radiography of the hospital institution in Cameroon, thus summarized the systemic interactions characteristic of the “sorcerer’s state” where finally, according to him, this permanent observation of the necessary questioning of society is essential whole, trapped in the socio-economic determinism that characterizes so much the operation of the various components of public service and State policy: “Nurses sick of the State, patients sick of nurses, State sick of the social management of the misfortune that it is in charge of, public health leads to questioning society as a whole. »11.

Fidèle K. AYENA observes for his part that: “the welfare state which prevailed until the 1980s still remains in the collective unconscious a common aspiration of populations when resorting to the public health service. But since the policies structural adjustment program (PAS) of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank from the 1980s, the welfare state which guaranteed everything to the citizen (vaccination, medicines, food aid), was transfigured in the imagination collective in “State sorcerer” who no longer does anything or can no longer do everything or has trouble providing for everything in all circumstances12”.

“The sorcerer state”, a metaphorical model of public administration management in several African countries including Benin, was the fate of purely administrative and non-inclusive and holistic planning of public service activities, particularly that of health, burdening thus the chances of the real taking into account of the protection of persons in all its dimensions. The acknowledgment of abandonment or being left behind was not only that a feeling. It was also a socioeconomic reality. The absence, at the time, of a regime of universal health insurance was an aggravation of the feeling of dereliction which animated the user of the public health service. The average Beninese had difficulty, in fact, in perceiving in the facts of what public financing of health corresponds to when health facilities public authorities were in fact facing enormous material difficulties. The situation of shortage of specialized human resources, dilapidation or extreme obsolescence of medico-technical and socio-sanitary equipment in most hospitals departmental offices (CHD), suggested in particular, for the average user, that the State would be finally resigned in front of his public health service mission. This reveals the thorny issue of health financing in the country, like other developing countries, as Isabelle COMBATTO13 explains in these terms: “The situation health of so-called developing countries generally gives rise to critical assessments. Many elements are used, on a recurring basis, to explain the difference between the sums invested in improving the health of populations and the results obtained. The alarmist speeches have indeed for a long time indexed the financial factors – lack of means or disastrous management available finances, technical problems, lack of personnel, health structures, equipment, politics, corruption, disengagement of States, imbalance in relations of North-South strength around health – or even cultural – archaism of beliefs, resistance cultural, poor receptivity to knowledge and biomedical techniques and, more broadly, in the face of exogenous innovations of which scientific medicine is a part”.

Adoption at community level of the international primary health care strategy (PHC) in the context of the global goal of Health for All by the year 2000, according to the WHO, since its Alma Ata Conference (1978), reinforced by the Bamako Initiative (1987), devoted the community contributions to self-financing14, particularly in essential drugs and medical consumables for care units. But this was not enough to restore everywhere the effective, efficient and effective presence of the public health service. The Strategy document of public health action and the various growth strategies for poverty reduction (SCRP) – highlighted the structural difficulties in the implementation of the PHC: “One of the major constraints to achieving health care goals remains the insufficiency of the financial resources necessary to carry out the investments in basic infrastructure, to ensure the management of health care primary school and make them accessible to the population. As long as households continue to bear more than half of health care costs, attendance goal health services and the control of priority diseases will be difficult to achieve. »15.

As evidenced by the situation in most health zones in Benin, the lack of of public health funding negatively impacts the organization of the area hospital, except when it is a private or denominational structure such as the Saint Zone Hospital Jean de Dieu de Boko, in the department of Borgou, whose sources of funding mostly private come from faith-based partners and households. Up to one recent period, the departmental hospital centers (CHD) which represent the level intermediary of health care provided by the public hospital, according to the health pyramid, concentrated a double phenomenon of desertion: on the one hand, the medical-technical desertion of its functional components leading, on the other hand, to the desertion of users who end up by turning to private structures or traditional healers. So the designs popular on the public hospital, actually took the state for a health funder public, a providential actor who, however, has undertaken to gradually renounce its commitments to protect citizens from diseases and all forms of prevention against threats to human life. The citizen was no longer solely responsible for the ways to provide for the constitution of its health capital. Its private resources to finance his health needs are now the only way for him to make up for the insufficiency structure of public health financing. The risk of illness, when it occurs, is borne entirely by the individual and by the spontaneous solidarities that his social or family status is able to mobilize. The quasi-systemic absence of a contingency mechanism or pooling of coverage of the financial risk of morbid episodes does not allow always to optimize public financing of health which, summoned to do everything, to cover everything, ends up fading before the achievement of the many objectives of the public health service. However, the State strives somehow to guarantee to every citizen his fundamental right to be cared for and to live in a healthy environment. Thus, the management of public health poses in all respects the thorny question of the infrastructures necessary for the proper functioning of the public health service. The solution to this question cannot be exclusively research and the provision of public financial resources. It exceeds, in fact, the pressure on these resources alone to take an interest in the very organization of the health system in its together. It also indexes the emergence of public policies intervening in synergy in the field of health and social development. Thus, for example, public policies of poverty reduction and particularly growth strategies for poverty reduction. poverty reduction (SCRP) would also be effective strategies for reducing certain causes of morbidity. Similarly, the gradual construction of a health insurance scheme (RAMU) (replaced in 2018 by another, broader and more ambitious one that is Insurance for the reinforcement of human capital) and free caesarean section in all obstetrical care trainings represent public policy measures implemented place to reduce the handicapping effects of the “witch state” on the image of the institution hospital. This aims to also restore the image of a state that is not a welfare state but above all concerned and manager of collective health and social development. Indeed, the State thus seems to better understand the public, social and economic interest in strengthening its upstream management policies for individual and collective health risk situations.

b.2: An incremental political evolution

Still in the context of writing this article, we carried out, from April 6 to 23, 2020, a high-level survey in order to better understand the evolution, over time, of public health action and the account of the protection of persons in this matter. As the target of the survey was essentially elite (senior executives in the sector and independent health experts), it took place in the first three major cities of the country, Cotonou, Porto-Novo and Parakou.

In addition to the general objective mentioned above, it was specifically about:

- reveal the level of consideration of the protection of persons in the framework of the development of the country’s institutional agenda;

- inventory the international and national legal instruments that govern the protection of people in terms of health on the one hand, and the knowledge of the actors (national officials, experts, health professionals and activists of consumer organizations of health services), somewhere else ;

- analyze the level of stakeholder involvement, from the design of public health policies to their implementation in the field.

The methodological approach followed is essentially descriptive in order to list and describe, with the people interviewed, the regulatory, institutional and professional situations in terms of the design of health policies. Then there was the analysis and interpretation of the results. The collection tool is an interview guide produced with the sphinx software.

The counting was done meticulously and the data processing was carried out using Excel 2016 software. This facilitated graphic illustrations of some results.

For these interviews, the choice of interviewees was made according to the position held, the profession and the number of years of experience in health action planning. At total, twenty-eight (28) senior managers took part in the survey, including health doctors public sector, health economists, former ministers still active or retired. All these people have an average of 25 years of professional experience. These twenty- eight people represent approximately 87% of the target, given the rarity in the field of executives and experts of this caliber, having actually taken part in programming processes and development of health strategy documents in Benin and in the west-west sub-region. African. The results of this survey enabled us to describe the major agendas country’s health policies as below.

b.2.1- Major health policy agendas

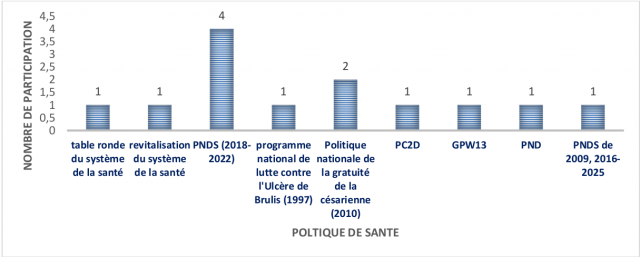

Figure 1: Participation of the target in the development of health planning documents

Source: Interview conducted by B.C. Dako, April 2020.

Figure 1 shows that 100% of interviewees participated in the development of the national health development plan (PNDS) (2007-2018); 50% participated in the design of the national policy on free caesarean sections (2010) and 25% contributed to the work of the round table on the health system, the revitalization of the health system, specific programs (national program against Burulis ulcer (1997), PC2D, GPW13, PND and PNDS from 2009, 2016-2025 This graph demonstrates the representativeness of the people interviewed and therefore the validity of the information collected during the study. investigation.

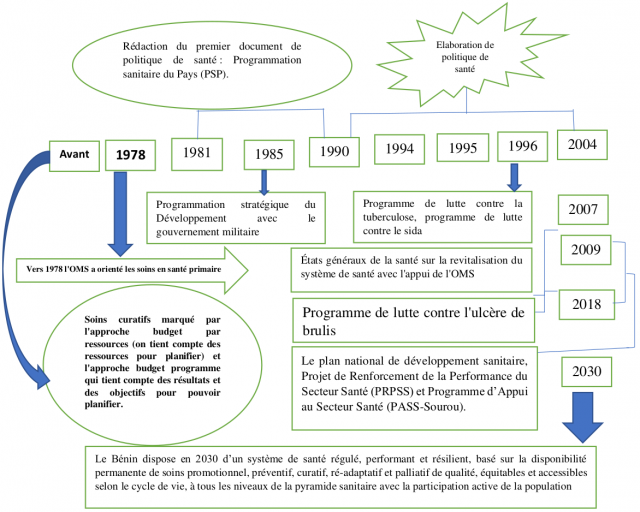

Figure 2: Evolution of health policies in Benin

Source: Field survey carried out by B. Dako, April 2020

Figure 2 summarizes the evolution of health policies in Benin over three periods. The period before 1978, that from 1978 to 2018 and that from 2018 to 2030. The country is indeed marked by different moments of its socio-political and health development.

Benin, formerly Dahomey, like most countries formerly under French colonial administration until 1960, the year of its independence, has experienced a gradual evolution of its action public health. Before August 1, 1960, the country did not know of any planning document of needs and resources to deal with diseases. The few existing health centers were mostly run by junior French professionals and native matrons responsible for administering primary care. No technical platform worthy of the name existed in the field to take charge of the major pathologies or epidemics that sometimes wreaked havoc in the event of an occurrence. It was a period of predilection for the pharmacopoeia, the populations turning massively towards traditional healers, if necessary.

This situation continued for several years after independence until 1978, when the WHO adopted the international strategy for primary health care (PHC) in Alma- Ata. Benin, having adhered to this Declaration, put in place, in 1979, a first national strategy document based on the Alma-Ata Declaration. Thus was born the first policy entitled Country Health Program (PSP) for the decade 1981-1990. The PSP, like the Declaration of Alma-Ata, essentially aimed at routine curative care in a particularly poor period and space where endemic diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and childhood illnesses (such as infections acute respiratory tract infections (ARI), diarrhoea, whooping cough, etc. But the effects of this PHC strategy were quite limited, due to the persistence of the causes of the said diseases in essentially underprivileged areas of sub-Saharan Africa.

The shortcomings of the PSP being felt very early on during its mid-term evaluation, the health authorities initiated, before the end of this program, its reformulation and its transformation into a more dynamic and ambitious strategy, taking into account its major shortcomings observed on the prophylactic and curative levels. This was the birth of the Health Development Strategy in 1985, in the midst of a Marxist-Leninist political regime.

At the end of the Health Development Strategy in 1990, a five-year plan was drawn up for the period 1991-1995, financed by the World Bank. This is the program of Development of Health Services (PDSS), designed and implemented concomitantly with the first Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) to which the country was subject, due to the major macroeconomic imbalances relating to hazardous public governance of revolutionary years. The PDSS has focused on the all-round construction of centers of health, but the recruitment and training of staff to lead them had not followed. In consequently, the technical platform necessary for the quality of health care not being adequate, fundamental reforms had proved essential to meet the needs growing health care for populations, which were bearing the full brunt of the social horrors structural adjustment programs. The World Bank, under harsh criticism against the PAS, agreed to finance in 1994, the first national meetings for the overhaul of the sanitary system. It was the Round Table on the health sector. These foundations gave birth of a specific program for the ten-year period. It was the first National Program development of the health sector (PNDSS 1995-2004).

The 1995-2004 PNDSS was truly the first health development program designed according to the international standard, with specific components corresponding to sub-programs relating to certain health problems experienced by the populations. These include the National Malaria Control Program (PNLP), the National Program for the Control of Onchocerciasis, the National Program for the Control of Leprosy, the National Program for the Control of Blindness, the National Program the fight against non-communicable diseases, the National Program for the Fight against HIV/AIDS, the Expanded Vaccination Programme, intended for the prevention of various pathologies threatening children aged 0 to 5 years in particular.

In 2007, during the 2nd generation of the PNDSS, the country organized its first assembly of the health sector to diagnose, once again, a sick sector notwithstanding the efforts made by the State and development partners to curb the difficulties. Indeed, the many specific programmes, plans and projects designed and implemented implemented continued to show their limits in the face of the ever-increasing health needs of populations. Benin unfortunately did not escape the dilemmas of African countries finding themselves between the grip of the continual dwindling of financial resources to adequately face the health challenges which are part of an increasingly exponential upward trend. In addition to the description of the history of political agendas, the survey also provided elements for assessing the consideration of the concept of personal protection in the development of various health plans and strategies.

b-2.2- Analysis of how the concept of personal protection is taken into account in the development of health policies

In the absence of a conventional definition, we propose, in the context of this article, an operational definition as follows: The protection of persons in terms of health can be understood as all the legal, institutional, administrative and taken by the health authorities to guarantee the optimal development of activities for the prevention of disease, the administration of care and the promotion of health, with a view to protecting populations against the risk of violation of their fundamental rights to health.

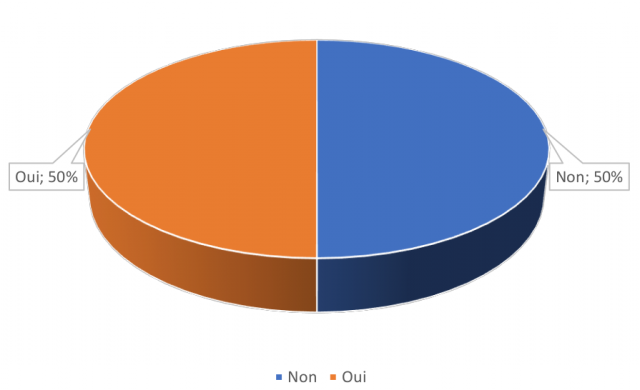

The analysis of Figure 3 below shows that 50% of people interviewed believe that the protection of people in good health, as defined above, is taken into account in health policies in Benin, while the other half thinks the opposite.

According to the first category of interviewees, health protection is rather perceived as all the social measures adopted by the State to allow people to seek treatment in the event of illness. It is therefore, for them, medico-social care by social security and health insurance, for well-defined targets. The protection of persons is also, for this category, all the actions carried out by the State and the local authorities to ensure the operation of public health services. This is the case with the acquisition of medical and health equipment for public hospitals, the updating of availability of human and financial resources, social security, the organization of health emergencies, free caesarean sections, care for indigent patients, etc. These are all arguments that justify taking into account the protection of healthy people in the various planning processes. For this category of respondents, the protection of healthy people is a strategic choice of the State to improve the state of health of the populations for which it is responsible, through various social measures. This one-dimensional vision of health protection is obviously narrow.

On the other hand, for the other half who think the opposite, the protection of healthy people is not explicitly written into health policy documents. For them, the care of a segment of the population, in this case the indigent, the development of a few specific programs or projects for assistance in the event of illness, in particular the National Program for the Fight against Malaria, the Expanded program of vaccination, free caesarean section, are not enough to deduce from the systematic consideration of the protection of healthy people in the development of public health policies and programs. And yet, the protection of healthy people has a much more significant meaning than these two categories of executives who design health strategies think.

Figure n°3: Consideration of the protection of healthy people in health policies in Benin

Sources: Interview conducted by B. C. Dako, April 2020

b.2.3- Meaning of the protection of people in health policies

For all the experts interviewed as part of this study, the protection of people in the development of health policies and programs is more or less known. It is, for the most part, confined to a single aspect: protection in terms of health insurance. For them, in fact, the concept of protection of health protection consists ensure financial accessibility to healthcare for populations, especially disadvantaged ones.

Taken in this dimension alone, they consider that several actions have been initiated and implemented, in particular the insertion, in the general budget of the State, of health care the free caesarean program for the reduction of maternal mortality, the creation of a co-payment for the management of part of the care for State agents and their families, the various programs designed and implemented to protect the most vulnerable of the population, in particular women, children and the elderly. This understanding of the concept of protection is narrow, given the many other aspects that this concept contains on the legal, technical and medico-social level. This inclusion of protection in such a dimension explains the lack of interest and its virtual non-existence in the various health programs, plans and projects, from independence to the present day.

C- Innovative political reforms and future prospects

From 2016, a new era opens in the Beninese health sector, with the strengthening of the legal and regulatory framework, the improvement of the governance of the sector, the reorganization the operation of health structures and training throughout the national territory, the modernization of hospital training through their endowment in state-of-the-art modern equipment, the gradual resolution of the shortage of personnel through the recruitment and training of competent professionals, etc.,

Indeed, in the new National Health Development Policy 2018-2030, the protection of healthy people seems to be placed in its multidimensional approach, reflected in the vision of the said policy expressed as follows: “Benin has in 2030, a regulated, efficient and resilient health system, based on the permanent availability of promotional, preventive, curative, re-adaptive and palliative care of quality, fair and accessible according to the life cycle, at all levels of the health pyramid , with the active participation of the population”. Six strategic orientations (SO) broken down into specific objectives and areas of intervention are defined. These are: (SO1) Development of leadership and governance in the health sector, (SO2) Service delivery and improvement of the quality of care, (SO3) Development of human resources in health, (SO4) Development of infrastructure, equipment, quality health products and

traditional medicine, (SO5) Improvement of the health information system, promotion of health research and innovation and (SO6) Improvement of financing for better universal health coverage.

But despite these promising structural reforms, difficulties in the field remain, which suggest that efforts remain to be made within the framework of the holistic protection of people’s health, now governed by law 2020-37 of February 3, 2021. It should be noted that the reforms undertaken in the Beninese health system aim to address the constraints of the sector in order to make it more efficient. This performance is measured through its continuous improvement, bringing into play the ability of institutional actors to anticipate16. In this logic, concerns related to the future of the health system arise despite the reforms. This is why we have carried out a strategic diagnosis of the health system being reformed, in order to identify key questions that can help explore possible futures and make the outputs generated by the said reforms reliable and sustainable.

Knowledge of the aspirations and problems of the actors during the reform period is necessary for an in-depth diagnosis. These problems were collected using a research with all categories of actors over a period of ten (10) years. These problems are presented according to the economic, social, political and technological level17.

Thus, on the economic level, the communities aspire to the improvement of purchasing power with a view to strengthening access to health services for all categories of actors. In effect, it appears from our investigations that not all social strata have sustained access to care due to the limited means to cope with daily expenses. To do this, the communities aspire to the generalization of the ARCH18 project throughout the national territory. Practitioners and administrative staff of hospitals aspire to an increase in resources, with a high point on the state subsidy.

On the social level, the actors aspire to continuous improvement, over the long term, of the quality of care for patients within health facilities. This assumes that public policies offer universal health coverage with sustained social support for the most disadvantaged. A community relay affirmed during the collection:

“People do not have the means to treat themselves, even when it comes to primary health care. As relays, we have been trained to provide them with first aid, but sometimes they do not even have the minimum to buy medicine. This assumes that the reforms that the state is making now do not benefit everyone. The problems are not completely solved at the base. It seems that there is an insurance now that the government wants to put in place, everyone must be able to benefit from this, whether we are in town or in the village. »

MENSAH D., community relay, interview carried out on 19/12/2021 at Allada.

From these remarks, we note that equity in access to health services is a major aspiration of the communities. As a result, the opinion that emerges postulates that the reforms have not not sufficiently taken into account all the categories of actors and all the aspects related to the constraints of the health system, which explains this type of problem in the analyzes that we carried out. However, more often than not, the people most vulnerable to disease are the same as those affected by gender inequality, social rejection or discrimination. The Global Fund and its partners plan to remove these barriers by investing in gender-focused human rights programs, fostering greater community participation in program design, implementation and monitoring. , and improving the financial sustainability of health services19.

The actors also aspire to an improvement in the working conditions of health workers. For some actors interviewed, the reforms are not accompanied by qualitative and quantitative staff reinforcement measures, and improvement of the technical platform. This deficit is deplored by a health worker, who argues that the lack of human resources is a source of poor performance:

“In my opinion, the new reforms have not solved the problems essential. It is not enough to tell people to work, but it is important to establish working conditions that can motivate the practitioner. A lot of things make me say that, but it’s especially the hourly mass that we are forced to do currently because of the lack of staff which makes me uncomfortable. In some hospitals like ours, we work on call, followed by on-call duty for 48 hours instead of 72 hours. We have families and this risks having a negative impact on the education of our children, because we no longer have the time necessary to supervise them. In these reforms, the government did not think of our families”.

Ruth A., nurse; interview carried out in a health center district of Cotonou on 20/12/2021.

These remarks reinforce the aspirations of health workers for a true health democracy against the backdrop of a highly participatory management of decision-making processes and the implementation of reforms. In addition, the communities also want a quality caregiver-patient relationship. Several beneficiaries of health services interviewed mentioned the poor reception in health centers, and believe that reforms must take into account the quality of services in public health facilities.

From a political point of view, the actors aspire to better governance of the health system through the recruitment of qualified personnel in sufficient numbers for training. establishment of a strategic watch to maintain and consolidate good practices resulting from the implementation of reforms.

On the technological level, the actors wish to strengthen the technical platform and the continuous supply of medical consumables in health facilities. It appears from the data collected that the technical platform of most hospitals is sorely lacking in the latest generation equipment. This is a situation that hampers adequate and timely patient care. A health worker from the hospital center academic Hubert K. Maga said:

“Even here, sometimes the scanner breaks down and patients are sent to private centers for their examinations. Given the standing of this hospital, I still believe that we lack the minimum, because it is supposed to be the reference center of the country. Admittedly, the reforms are commendable, but the government must make more efforts to equip health facilities. It is not enough to want to build new hospitals, but we can already strengthen the existing ones…”

H. C., health worker, interview conducted on 17/12/2021 at CNHU-HKM from Cotonou.

These remarks demonstrate the position of the practitioners on the relevance of the reforms. Strengthening the capacity of health facilities to meet the needs for quality care is a major aspiration of the actors within the framework of the reforms.

But these different aspirations are not limiting. Other problems remain. The economic problems mentioned by the actors are generally related to the low purchasing power of the communities. This issue is a major obstacle to access to basic health services. Geographic inaccessibility was also highlighted by actors as an important social concern. In the same vein, they mention constraints related to the quality of care, emphasizing the poor reception in some health facilities. For the actors, the reforms must take into account the control and the quality assurance of the care which begin with the good reception at the hospital, the first link of the relational chain of the course of care. The objective of good reception is to establish a relationship of mutual trust, security and help for the patient. Well executed, it reassures the patient and facilitates continuity of care20. In this regard, the surveys we carried out in April 2020 have already revealed the following:

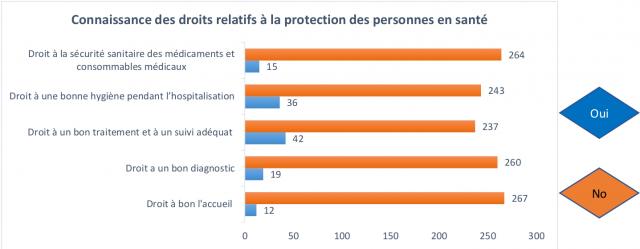

Figure 4: Knowledge of the protection rights of healthy people

Source: Field survey, B. C. Dako, April 2020.

The figure above reveals that the majority of health professionals practicing in the field do not have a clear knowledge of the various legal items related to the protection of healthy people in hospitals. These include the rights to a good reception, to a good diagnosis, to treatment and adequate follow-up, to good hygiene during hospitalization, to the health safety of medicines and medical consumables. Specifically, the results look like this:

- right to a good reception: 267 health professionals have a very vague notion of what that reception is a right of patients while 12 consider it a fundamental, i.e. 95.70% and 4.30% respectively. These figures reflect the idea that professionals, in their majority, really do not know how to apply the right reception of the sick as a recognized right of the latter;

- right to a correct diagnosis: concerning this item, 260 people, i.e. 93.19% of those interviewed, also have a very vague notion of the correct diagnosis as one of the recognized rights of patients, while 19 of them, i.e. 6.81%, recognize it as Phone.

- right to good treatment and adequate follow-up: on this item, 237 people, i.e. 84.95%, do not understand that good treatment and personalized follow-up of patients constitute rights in health facilities, while 42 of them, i.e. 16.05 % only, feel they know little. This relatively high rate is worrying because of its potential impact on patients because the treatment and personalized follow-up of patients constitute the basis of optimal care in any health facility. and a guarantee of protection in a health environment.

- Right to good hygiene during hospitalization: overall, 243 people, i.e. 87.10%, understand as vaguely that good hygiene in a hospital environment is a guarantee of health security for patients, especially those in hospital, while 36 of them, i.e. 12.90%, have a more or less good knowledge of it.

- Right to health safety of medicines and medical consumables: the surveys showed that 264 people, i.e. 94.62, are also unaware that the safety of medicines and medical consumables is a fundamental human right. patients in hospitals because some of them even engage in the illicit trade in counterfeit medicines, and only 15 people, or 5.38%, recognize that the quality of medicines and consumables depends on the continuation of the treatment and disease progression.

According to the results described above, the relatively overwhelming proportion of people interviewees with a very vague knowledge of the items of this component of protection people, would be due, in fact, to the cognitive shortcomings linked to their basic training, which would not have sufficiently integrated these important dimensions into the training curricula. These high proportions of agents confirm the daily realities experienced by users of the public health facilities and, more specifically, patients and their companions.

The political problems are linked to weaknesses in the governance of the health system and the non-existence of a strategic monitoring mechanism for the sustainability of the achievements of the reforms. From the technological point of view, there is the weakness of the technical platform of health establishments and the shortage of medical consumables. We are still observing major trends despite the reforms in the sector.

The analysis of the aspirations and problems of the actors as well as the triangulation of the data collected make it possible to identify the governance of the health system as a major theme, which should be the subject of an in-depth study in order to identify the key variables that structure the Beninese health system. Indeed, concerns related to the accessibility of communities to health services, the quality of care offered and the technical platform, all revolve around the governance of the health system.

The strategic diagnosis makes it possible to identify the flow of variables that structure the system and the actors who interact according to the challenges and issues inherent to the system, on the other hand, and to the actors, on the other hand. Therefore, it consists of identifying the key variables through a retrospective analysis conducted here using a SWOT matrix (in the table below), highlighting the strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

Table 1: SWOT matrix of health system governance in Benin

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

| Opportunities | Threat |

|

|

Source: Field data, December 2021.

The analysis of this strategic diagnosis matrix on the basis of the SWOT makes it possible to better understand the dynamics of the system being reformed with the various constraints to which it is subject. The key variables that structure the system show a preponderance of the political will of the governors which is manifested by the reforms initiated since 2016. But the implementation of these reforms does not systematically guarantee the performance of the health system because aspects related to geographical accessibility and economy, the strengthening of the technical platform and the quality of services persist. The external variables show a strong dependence of the system on PTFs, with government initiatives aimed at strengthening access to care which remains, despite the progress, still limited. It is also noted a still fledgling collaboration between the biomedicine specialists and traditional healers despite the legal recognition of these last 21.

In order to understand the possible prospects of the system for the next decade, we carried out an exploratory analysis aimed at identifying the positioning and interactions between variables and actors. To this end, the structural analysis from the variables and the study of the play of the actors have made it possible to identify the key questions for the future, making it possible to build the possible system scenarios. The list of key variables (internal and external) used as basis for the structural analysis comes from the strategic diagnostic matrix above, which itself stems from an in-depth study of the said matrix. Our structural analysis pursues two complementary objectives, namely:

- ensure as exhaustive a representation as possible of the system studied;

- reduce the complexity of the system by retaining only the essential variables22.

The table below provides the list of the various internal and external variables retained for the analysis of the system.

Table 2: List of key variables (Source: field data, December 2021)

| N° | Long title | Short title |

| 1 | Results-Based Budget Management Reforms | RéfGAR |

| 2 | Political will of institutional actors | VolPol |

| 3 | Existence of a ten-year health policy | ExiPol |

| 4 | All of the reforms and restructuring actions of the health system from 2016 to date | Reforms |

| 5 | Appropriation of new technologies pharmaceutical, digital and managerial | AprNTIC |

| 6 | System for monitoring and regular control and assistance of the Ministry of Health | SuiviEv |

| 7 | Existence of competent and qualified executives | ExiCadr |

| 8 | Quantitative and qualitative lack of resources human | MankRH |

| 9 | Difficulties in accessing care for some communities | DifAccès |

| 10 | Recurring shortages of medical consumables | RupMédi |

| 11 | Partial dependence of the system on PTFs | DépPTF |

| 12 | Technical platform still unsuitable | PlaTech |

| Variables externes | ||

| 13 | Reaffirmed support from TFPs | ExiPTF |

| 14 | Adoption of the ARCH project in 2019 | ARCH |

| 15 | Involvement of local communities | ApLocal |

| 16 | Biomedicine and endogenous knowledge collaboration | MédEndo |

| 17 | Dwindling of TFP financing | DimuPTF |

| 18 | Insufficient resources allocated by the State to hospitals | SouEtat |

| 19 | Low purchasing power of communities | PouvAcha |

| 20 | Abolition of the indigent health fund | SuprFSI |

| 21 | Sociocultural burdens | PezSocio |

A simulation of the evolution of these twenty-one (21) variables is carried out in a systemic approach with the presumption of a strong interweaving of each other, no variable being able to truly function alone without the others. Thus, our structural analysis is carried out according to the theory of games or choices in an uncertain universe, from a simulation of the evolution of one variable in contact with another or all of its pairs within the system. system. All in all, we related the variables selected in a double-entry table23. Crossing two by two of the variables in the structural analysis matrix allowed us to understand those that turned out to be the most influential (driving) or the most dependent on the system.

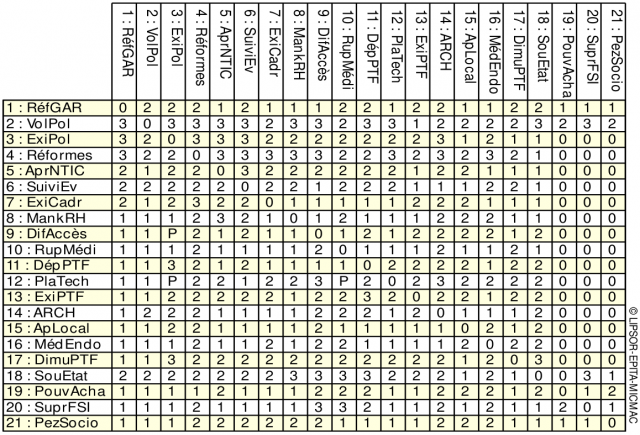

Table 3: Structural analysis matrix

Source: Micmac, field data, December 2021

Influences are scored from 0 to 3, with the option to flag potential influences:

- 0: no influence

- 1: Low influence

- 2: Medium influence

- 3: Strong influence

- P: Potential influence.

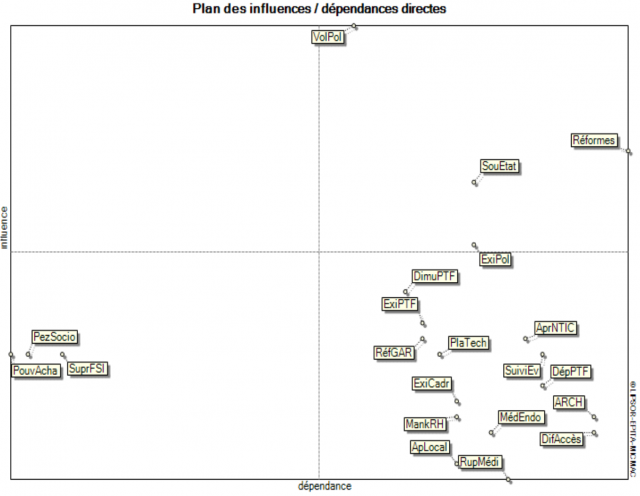

The interpretation of the results of the structural analysis is obtained from the motricity-dependence graph which makes it possible to distribute the variables by sector, according to the intensity of their dependence and/or influence. This gives the following plan:

Figure 5: Map of direct influence/dependency

Source: Micmac, Field data, December 2021.

On reading this graph and following the interpretation grid of GODET M.24, it emerges:

- Autonomous variables

These are variables that develop autonomously with little or no connection with the other variables. These are socio-economic constraints, the purchasing power of communities and the abolition of the indigent health fund.

- Result variables

These variables are not very influential and very dependent. In this case, it is the existence of a national health policy, the support of TFPs and the reduction of their contributions,

the weakness of the technical platform, constraints related to geographical and economic accessibility to community health care.

- Relay variables

Still called stake variables, they are very driving and very dependent. Those are relatively malleable variables, and any action that takes place there will automatically impact the others with, possibly, retroactive effects on themselves. We can find in this category issues related to political will, reform initiative and state support to health facilities.

But understanding the dynamics of the Beninese health system requires a good understanding of the interactions between the actors. This step consists in presenting, on the one hand, the balance of power between the actors and, on the other hand, their positioning on the objectives. The actors selected for this analysis are listed in the table below, with the change objectives pursued by each of them.

Table 4: List of actors and their change objectives

| N° | Actors | Abbreviated actors | Change Goals | Objective abbreviated |

| 1 | Technical and financial partners | PTF | Provide technical and financial support | AppuiTF |

| 2 | State25 | State | Ensure universal access to health services and better quality of health care | Acè_Univ |

| 3 | Health workers | Agent_Snt | Caring for patients properly | Cared for |

| 4 | Users of health establishments | Users | Meet health needs | Sat_Bes |

| 5 | Civil society | Soc_Civ | Defend the interests of communities in terms of public health |

Déf_int |

| 6 | Administration of hospitals | Adm_Hop | Providing quality care to communities | SoinKali |

| 7 | Association of traditional healers | tradiPrt | Promotion of endogenous knowledge | Sav_Endo |

Source: Mactor, field data, December 2021.

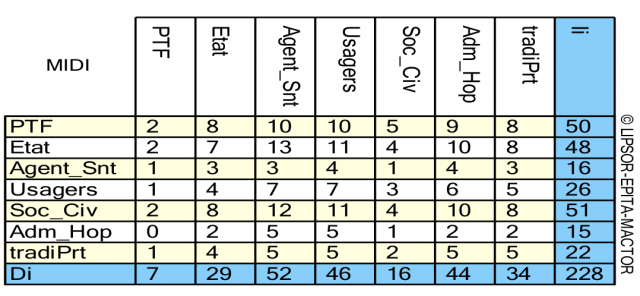

For the analysis of the actors’ play, the Mactor software was used. The degree of influence between the actors of the system is materialized in the matrix of direct and indirect influence as shown in the matrix below:

Table 5: Matrix of direct and indirect influence of actors

Source: Mactor, field data, December 2021.

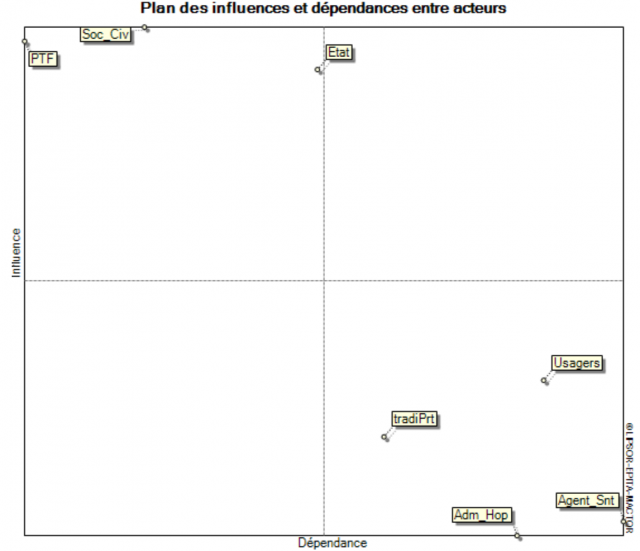

The values represent the direct and indirect influences / dependencies of the actors on each other: the higher the number, the greater the influence / dependence of one actor on another. The powers come from different logics of the actors and cannot be linked by simple hierarchical relationships26. As part of this research, the actors position themselves according to their interests and the power they embody. Thus, they influence each other and these influences are represented through the plan below:

Figure 6: Plan of influences and dependencies between actors

Source: Mactor, field data, December 2021.

This graph presents the positioning of actors in the system, through power games. It is easily noticed that the dominant actors are the TFPs and civil society. The state positions itself as a relay player, i.e. it is both very influential and very dependent of the system.

These actors pursue several objectives, the degree of which differs from one actor to another. An analysis of the evaluation of the mobilization of the actors on their respective objectives in order to identify their commitment was made. It follows that universal access to health care and meeting the needs for quality care are the most important objectives for the actors. Based on the revealed importance of the actors’ commitment to their change objectives, we have highlighted the intensity of the convergences between these actors in relation to their respective objectives. This has made it possible to highlight below (in figure 7) the possible interactions between the said actors.

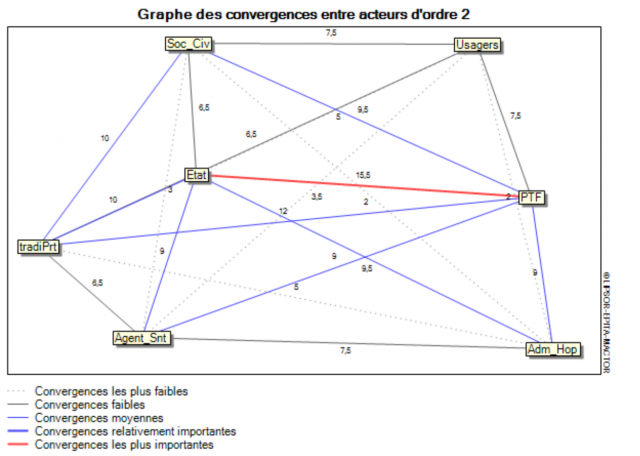

Figure 7: Convergence graph between actors.

Source: Mactor, field data, December 2021.

The most significant convergences are those noted between TFPs and the State. It follows that these two actors are part of a similar logic. Despite the almost non-existence of divergence between actors, the convergences here seem relatively weak between some of them, such as the hospital administration and traditional healers. What confirms the empirical observations on the relationship between these two actors in the itinerary treatment of patients in Benin.

The exploratory analysis of the reforms undertaken makes it possible to identify the relationships between the variables, the balance of power between the actors of the system as well as their mobilizations or commitment to goals. Therefore, a question remains: What are the challenges and major issues that the Beninese health system could face in the years to come.

come ? The answer to this question should make it possible to highlight the capacities anticipation of actors in the face of endogenous or exogenous shocks that may test the resilience of the system in the future. To this end, we have analyzed the four key concerns27 already identified in terms of issues and challenges for the actors. It is :

- Governance of the health system;

- Anticipation of the dynamics induced by the reforms;

- Resource Mobilization;

- Accessibility to health services.

These four key concerns have been crossed with the possible hypotheses to be determined below. afterwards in order to identify possible scenarios for the next decade. This is the place to remember the role of foresight, which consists in helping the various actors and decision-makers to understand and to make choices for relevant decisions in terms of social utility, feasibility, effectiveness and efficiency. It is to this exercise that the following section of the this diagnostic study. It is indeed a question of predicting the hypotheses of the possible future at through the identification of scenarios and the formulation of a shared vision. Concretely, we assessed the consistency, likelihood and cost/benefit of the possible scenarios of the Beninese health system oriented towards the protection of people to, finally, choose the most relevant and the related vision. All this, with regard to the aspirations of the actors, the variables driving forces, inertia and power relations between actors.

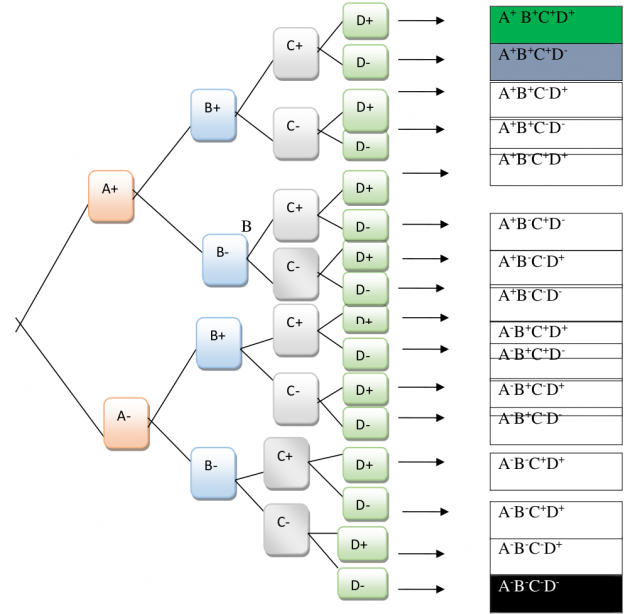

To determine the scenarios, two methods were exclusively retained for the various key concerns: one corresponding to a favorable evolution of the situation and the other to an unfavorable development. Thus, a set of hypotheses corresponds to n questions, each represented by one or other of its modalities, i.e. the favorable situation or the unfavorable one declined as follows:

- A+ Corresponds to a favorable development of key question A

- A-Corresponds to an unfavorable evolution of the key question A

- B+ Corresponds to a favorable evolution of key question B

- B- Corresponds to an unfavorable evolution of the key question B

- C+ Corresponds to a favorable evolution of the key question C

- C- Corresponds to an unfavorable evolution of the key question C

- D+ Corresponds to a favorable evolution of the key question D

- D- Corresponds to an unfavorable evolution of the key question D

In total, sixteen (16) sets of hypotheses are obtained from the combinations of the key questions as presented in the decision tree below:

Figure 8: Decision tree

Source: research data, December 2021.

From the point of view of coherence, likelihood and probability, the examination of the sixteen (16) sets of hypotheses resulting from the decision tree made it possible to retain three scenarios including an ideal scenario (n°1 ), a realistic (n°2) and a catastrophic (n°3). The table below shows the structure of these three scenarios.

Table 8: Analysis of scenarios for 2031

| Key questions | Hypothesis game 1

(Scenario 1) |

Hypothesis game 2

(Scenario 1) |

Hypothesis game 3

(Scenario 1) |

| Health system governance | Good governance of the health system | Good governance of the health system | Bad governance of the health system |

| Anticipation of the dynamics induced by the reforms | Proactivity of actors | Proactivity of actors | Actor passivity |

| Resource mobilization | Strong resource mobilization capacity | Strong resource mobilization capacity | Weak resource mobilization capacity |

| Accessibility to health services | Total coverage of health care needs health |

Low coverage of health care needs | Low coverage of health care needs |

| Scenario names | Wéziza28 (light) | Lanmesian (good health) | Zinflou (darkness) |

Source: research data, December 2021.

If the Zinflou scenario (darkness) which means that all health indicators are red and that this approach is not at all possible in the current context of massive reforms in the health sector, the Wéziza scenario is, on the other hand, extremely optimistic. It appears like the best health situation that one could hope to have and puts all the health indicators at the Green light. But at the same time, this scenario seems too good to be realistic. In effect, the basic hypothesis “Total coverage of the health care needs” of the populations seems unrealistic in the socio-economic and political conditions of Benin in the space of ten years. Total coverage of health care needs is a public health impact that falls within the scope of a dynamic process and the conjunction of sustained efforts to improve the system over a long term; which does not seem obvious, due to political and economic constraints and equally important challenges relating to other sectors.

As for the Lanmesian scenario, it seems closer to reality. It consists of four basic assumptions which are: Good governance of the health system; Proactivity of actors; Strong resource mobilization capacity and poor coverage of needs in health care. It is a scenario of hope that encourages initiative and action to work more to the densification of health infrastructures with a view to the continuous improvement of geographical and financial accessibility of populations to health care. His choice seems here the closest to socio-economic and political realities, with regard to the reforms undertaken and aspirations of the actors studied above. To this end, the strategic vision that emerges is stated as follows:

Benin’s health system is, in 2031, well governed, with a strong capacity for anticipation and mobilization of resources by the actors with a view to universal health coverage.

This vision will be achieved through relevant strategies, carrying innovative actions, with proven socio-economic benefits. In other words, it is a question of transforming this vision into a contextualized reality, thus contributing to the sustainable development of the system, in view of the reforms that have marked it over the past five years.

Conclusion

Benin, a country located in Africa south of the Sahara, is not immune to political, structural and economic difficulties in the design and implementation of solid policies for the health of populations. Strongly influenced at the start by the meager colonial and post-colonial heritage, pro-personal health policies only really took off in the early 1980s with the launch of primary health care ( SSP) adopted in 1978 during the WHO Conference in Alma Ata. Notwithstanding the will displayed by the political authorities and the actors at various levels, the health policies and organization have not been able to withstand the pangs of the colossal economic and social challenges of the country, culminating in the continuous reduction financial resources to health. From 2016, a glimmer of hope opened up in the health sector, like all the other sectors of national life. Massive investments are underway, necessitated by major structural reforms of the whole system. Positive results are expected, according to forecasts for the implementation of the National Health Policy 2018-2030. However, in view of the results of a diagnostic study carried out as part of the preparation of this article, it follows that the question of governance is posed as a major challenge. It arises in terms of the effective mobilization and involvement of all the players in the sector, on the one hand, and the rigorous management of material and financial resources dedicated to health, on the other. On this major challenge depends the achievement of the strategic objective that constitutes the universal health coverage of the population, and therefore the holistic protection of Beninese communities in the field of health.

1 LEMIEUX Pierre, BERGERON Clermont, BEGIN and Gérard BELANGER, (eds.), The health system in Quebec. Organizations, actors and issues. Chapter 5, p. 107-128. Quebec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1994, [online] available in “Classics of Science social.

2 MASSÉ Raymond, “Public health as a political project and an individual project. », in Bernard HOURS, (dir.), Systems and policies of health. From public health to anthropology, [online], text available in “Classics of social sciences (Jean-Marie TREMBLAY) », op. cit., p. 6.

3 Comparable Africa? Public health and global security in Benin, Doctoral thesis in Political Science, defended by Fidèle Kadoukpè AYENA, University of Toulouse, May 2012.

4 Mathieu Kérékou was President of the Republic, at the head of a Marxist-Leninist regime, from 1972 to 1990. the historic Conference of the Living Forces of the Nation in February 1990 followed by the first five-year term of the democratic renewal of Nicephore Soglo (1991-1995), he returned to power, democratically elected, for two terms (from 1996 to 2006).

5 Emmanuelle Kadya TALL, “Democracy and Voodoo cults in Benin”, in Cahiers d’études africaines. Flight. 35 N°137, Democracy in Decline. p.p. 195-208. 1995, p. 4 [online] available on Persée, http://www.persee.fr.

6 Wim Van LERBERGHE and Vincent de BROUWERE, “State of health and state health in sub-Saharan Africa” in Marc-Éric GRUÉNAIS and Roland POURTIER, (dir.), Health in Africa. Old and new challenges, pp. 175-190. Contemporary Africa, Special issue, Quarterly N° 195 July-September 2000, La documentation Française, p. 180.

7 HASSENTEUFEL, Patrick, “Do policy networks matter? Descriptive facelift and analysis of the interacting state”, in Le Gales, Patrick et THATCHER, Mark, (dir.), Public policy networks: debates around policy networks, Harmattan, 1995, 272 p.

8 Public health and global security in Benin, Doctoral thesis in political science, defended by Fidèle Kadoukpè AYENA, University of Toulouse, May 2012.

9 Joseph TONDA and Marc-Éric GRUÉNAIS, “African medicines and the prophet syndrome” pp. 273-282; in Marc-Eric GRUENAIS and Roland POURTIER, (dir.), “Health in Africa: old and new challenges”, Contemporary Africa, Special issue, Quarterly N° 195, op. cit., p. 282.

10The Republic of Benin, formerly Dahomey, gained independence on August 1, 1960.

11 Bernard HOURS, The Wizarding State. Public Health and Society in Cameroon, Collection: Knowledge of Men, Paris, the Harmattan, op. cit., p. 159.

12 Fidèle K. AYENA, comparable Africa? Public health and global security in Benin, doctoral thesis in political science, May 2012, University of Toulouse, page 368.

13 Cf. Isabelle GOBATTO, “Doctors as actors in health systems. A case study in Burkina Faso » pp. 137-162, in Bernard HOURS, (ed.), Health systems and policies. From public health to anthropology, Paris, KARTHALA, 2001, op. cit., p. 137.

14 In Edgard-Marius OUENDO, Michel MAKOUTODÉ, Victoire AGUEH and Ayité MANKO D’ALMÉIDA, “Equity in the application of the Bamako Initiative: situation of health care for indigents in Benin and approach to a solution” pp. 119-129, in Martine AUDIBERT, Jacky MATHONNAT and Éric de ROODENBEKE, (dir.), Health financing in low-income African and Asian countries income, op. cit., p. 120.

15 Republic of Benin, “Growth Strategy for Poverty Reduction, SCRP”, final version, April 2007, op. cit., p. 16 out preliminary pages.

16 World Health Organization, Health Systems Performance Assessment, Secretariat Report, December 2000

17 We are studying health here as a total social fact, but in his work, the current vocation of sociology, Georges Gurvitch considers that it is necessary to apprehend the social fact in all the fields of activity of the man that he delineates across the economic, social, political, environmental, cultural and technological (ESPECT) system. We choose to limit ourselves to the economic, social, political and technological levels because according to empirical data and readings, the variables that structure the Beninese health system with the advent of reforms are concentrated on these levels.

18 The Insurance Project for the Strengthening of Human Capital (ARCH) was born from the reforms undertaken from the start of the implementation of the Government Action Program 2016-2021.

19 Global Fund, Universal Health Coverage in Focus, May 2019 Report, p.3.

20 Doctor CHAOUI Hanane, Reception of the user at the public hospital. Case of the Specialty Hospital in Rabat, Dissertation at the end of the specialization cycle in public health and health management, National School of Public Health Morocco, 2017, pp. 20-21.

21 See Articles 72 to 73 of Law 2020-37 of February 3, 2021 on the protection of human health in the Republic of Benin.

22 GODET M., 2005, developing a strategic forecast, Paris, IAAT, p11-12.

23 This is the structural analysis matrix whose rows and variables correspond to each of the variables identified

24 GODET, 2005, op cit, p.12.

25 This is the state in its broad dimension, government, political authorities and technical staff of ministries and all state structures.

26 Jean-Luc Piermay, “Local dynamics and powers in central black Africa: an opportunity for urban management? in JAGLIN S. and DUBREEON A (dir), Power and cities of black Africa: Decentrations in perspective, Paris, Karthala, 1993, pp.285-294.

27 These four key concerns were expressed by the actors during the field survey in December 2021.

28 The names given to the three different scenarios, namely Wéziza, Lanmèsien and Zinflou, are concepts in the Fon national language, spoken in a large majority of southern Benin.

Bibliographic references

Bernard HOURS, The Wizarding State. Public Health and Society in Cameroon, Collection: Knowledge of Men, Paris, Harmattan;

Doctor CHAOUI Hanane, Reception of the user at the public hospital. Case of the Specialty Hospital in Rabat, End-of-study dissertation for specialization in public health and health management, National School of Public Health Morocco, 2017;

Edgard-Marius OUENDO, Michel MAKOUTODÉ, Victoire AGUEH and Ayité MANKO D’ALMÉIDA, Equity in the application of the Bamako Initiative: situation of health care for indigents in Benin and solution approach; in Martine AUDIBERT, Jacky MATHONNAT and Éric de ROODENBEKE, (dir.), Health financing in low-income African and Asian countries, op. cit., ;

Emmanuelle Kadya TALL, “Democracy and Voodoo Cults in Benin”, in Notebooks of African Studies. Flight. 35 No. 137, Declining democracy, 1995, [online] available on Persée, http://www.persee.fr;

Global Fund, Universal Health Coverage in Focus, May 2019 Report;

GODET M., 2005, developing strategic forecasting, Paris, IAAT;

HASSENTEUFEL, Patrick, Do policy networks matter? Descriptive facelift and analysis of the State in interaction”, in Le Gales, Patrick and THATCHER, Mark, (dir.), Public policy networks: debates around policy networks, Harmattan, 1995;

Isabelle GOBATTO, Doctors actors in health systems. A case study in Burkina Faso”, in Bernard HOURS, (dir.), Health systems and policies. From public health to anthropology, Paris, KARTHALA, 2001;

Jean-Luc Piermay, “Local dynamics and powers in central black Africa: an opportunity for urban management? » in JAGLIN S. and DUBREEON A (dir), Power and cities of black Africa: Decentrations in perspective, Paris, Karthala;

Joseph TONDA and Marc-Éric GRUÉNAIS, African medicines and the prophet syndrome, in Marc-Éric GRUÉNAIS and Roland POURTIER, (dir.), Health in Africa: old and new challenges, Contemporary Africa, Special issue, Quarterly N° 195;

LEMIEUX Pierre, BERGERON Clermont, BEGIN and Gérard BELANGER, (dir.), The health system in Quebec. Organizations, actors and issues. Chapter 5, Quebec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1994, [online] available in Classics of the social sciences;

MASSÉ Raymond, Public health as a political project and an individual project, in Bernard HOURS, (dir.), Health systems and policies. From public health to anthropology, [online], text available in The classics of social sciences (Jean-Marie TREMBLAY);

Republic of Benin, Growth Strategy for Poverty Reduction, SCRP, final version, April 2007;

Wim Van LERBERGHE and Vincent de BROUWERE, State of health and state health in sub-Saharan Africa, in Marc-Éric GRUÉNAIS and Roland POURTIER, (dir.), Health in Africa. Old and new challenges, Contemporary Africa, Special issue, Quarterly No. 195 July-September 2000, French documentation;

Comparable Africa? Public health and global security in Benin, Doctoral thesis in Political Science, defended by Fidèle Kadoukpè AYENA, University of Toulouse, May 2012.