Author: Benjamin Coovi DAKO, PhD

Doctor in Political Science, Public Policy Analyst

Expert in Health, Professor of Health Policy at the National School of Administration and the

and the Doctoral School of Legal, Political and Administrative Sciences from the University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin.

“Improving health in Africa faces many challenges. The financial resources devoted to it are insufficient, but increasing them does not enough. It is essential to strengthen health systems and improve efficiency health expenditure, public and private. In most countries, constraints the budgets are strong, but there is room for maneuver to reinforce the public spending on health, whether from domestic funding or foreign aid. However, particular care should be taken with regard to the effects that may possibly result in different elements that are brought into play an important role in improving health. States must use with relevance all the possibilities of increasing the health expenditure of which they can have. Most of them cannot afford to neglect the direct payments, but these must be integrated into a financing strategy coherent, carefully analyzed and implemented”1.

This quote from MATHONNAT, J. teaches us about the importance of health financing on the one hand, the need to initiate innovative strategies for mobilizing resources to dedicate to it and efficient management mechanisms of said resources for the promotion equitable and universal access to health care, on the other hand. In this article, In the first part (A), a brief review of the major global models will be discussed. health financing; in a second (B), wanderings of financing strategies of health in Benin from 1970 to 2016 will be analyzed and, in the third part (C), will be illustrated the governance in progress since 2016 for resilient and sustained health financing, in a context of politically displayed protection of populations.

A- Major global health financing systems

“The history of health systems in developed countries shows that at different times, all countries shared similar health goals (helping the sick poor, guarantee a replacement income for sick employees and, for Europeans, guarantee access to care for all), but have chosen different answers”2.

This statement by Bruno Palier points to the existence of differences characterizing the health systems in the world, from which derive health financing methods. These differences arise in particular from the type of institutions handling the demand for care (State, collective health insurance, mutual insurance, private insurance); fashion organization of the supply of care (place of public hospitals, role played by doctors generalists, etc.) and that of the medical professions developed in the past (the importance of liberal medicine).

These differences also reflect the plurality of priorities selected for each system: the universality of health coverage for some, the choice of doctor, of the establishment of care and maintenance of liberal medicine for others, the priority given to the market in the case of the United States. Taking these considerations into account, it emerges today, according to Bruno Palier, three main types of health systems in developed countries, even in the world namely:

✓ National health systems ― (Great Britain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Spain and partly Portugal, Greece, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) ― which are organized as a public health service and provide virtually free access to healthcare for all citizens in order to guarantee universal health coverage.

✓ Health insurance systems ― (Germany, France, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Japan, Netherlands, some Central and Eastern European countries). ― The offer care is partly private (ambulatory care, certain hospitals or clinics), partly public part (a large part of the hospital sector in particular) and guarantees the most often the choice of doctor for the patient, as well as the status of liberal medicine.

✓ Liberal health care systems ― (mainly that of the United States, but also those of certain countries of Central and Eastern Europe or of certain countries of America Latin). ― The public health protection system is very partial. Only people in need of urgent care, the poorest, the elderly and the disabled enjoy public health support, all others should use a private insurance system, most often financed by employers.

In the application, the results obtained vary from system to system. National systems generally guarantee great equality of access to care and levels of relatively low health expenditure; but they can provide a questionable quality of care and are mainly characterized by very long queues before being able to access care specialized. Health insurance systems make it possible to guarantee the choice of the patient, care facility, comfort and often the quality of care, but this is the most often at the cost of high health costs, and sometimes of unequal access to care. the American system is very efficient technologically and allows the wealthiest to have access to the best care; but it is also characterized by very strong inequalities (in access to care as in the state of health of the population) and an overall level of health expenditure paradoxically very high.

Despite the existence of these globally proven models that can serve as a reference for developing countries, African countries including Benin are always striving to seek the right innovative, resilient and sustainable financing mechanism to cover the needs of health of their populations. But for decades, the country’s experience seems away from this requirement.

B. The Beninese health financing experience from 1970 to 2016: strategic wanderings

In an international context of permanent challenge of controlling the financing of the health of populations in developing countries, Benin, a country recently declared low income intermediary according to the World Bank3, must set up an appropriate and resolutely oriented towards the major health challenges resulting from the political will of protection of human health.

Prior to the establishment of primary health care (PHC) in the early 1980s, public health expenditure fell within the exclusive domain of the state. But after the advent of the Bamako initiative4, these expenses were transferred to the communities which ensured their financing by recovering the cost of services from consumers. HAS To this end, in Benin, commune management committees (COGEC) and community management committees borough (COGEA) have been put in place. These bodies were to ensure the promotion and development of community participation in health activities. These committees managed the administrative and financial problems of health facilities in the municipality or of the borough. For a health center to be financially viable, it had to reach a minimum recovery rate of 1.2 (i.e. the ratio between revenue and expenditure related to the services provided). This rate is fragile if it is between 1 and 1.2 and in deficit if it is less than 1. At appraisal, no department had ever achieved the sustainability rate, the best being 1.13 in 2006 in the Zou5. The distribution of revenue on financing community in the same year listed drugs as the main source of revenue with more than 2/3 of Community revenue. Some services were not accessible or even available in all health centers; this was also the case for the laboratories or radiology centres6.

The persistence of these problems, which have become structural, is linked to the serious difficulties of health financing from which Benin has suffered since its accession to independence. However, the financing of health systems has become in the 21st century an essential element of the universal coverage7.

According to the 2010 WHO Health Expenditure Atlas, Benin spent about US $275 million for health, or US$ 31 per capita. This figure was below the minimum recommended (US $44). This situation is explained, among other things, by the non-regular assignment of resources available for priority interventions with high health impact. Furthermore, the organizational and institutional redundancies between the health sector and that of finances did little to promote adequate and timely consumption of those resources.

In order to reverse this trend and improve the situation in a lasting way, Benin has implemented puts in place a subsidy mechanism allowing free treatment for certain diseases (HIV infection, tuberculosis, kidney failure, malaria in children from 0 to 5 years and pregnant women, medical evacuations and substantial support for certain vulnerable categories of the population such as the poor. During several decades, this country, like so many others south of the Sahara, has implemented the strategy of results-based financing (RBF), as part of strengthening the performance of the health system. The RBF experience was intended to further motivate health workers to provide better quality care and services.

The advent of the universal health insurance scheme (RAMU) in 2010 led to the pooling of the various existing mechanisms, to attempt universal coverage at the whole population. But the insufficient results of this diet show the shortcomings institutional and organizational at the basis of its design.

The direct consequences of this institutional dysfunction have long impacted the health financing structures whose weight rested essentially on households. He has in fact been observed in the country, during the period under review, four main sources health financing: households (52%), the State (31%), local authorities (less 1%) and technical and financial partners (16%)8. Households, having during long been the main contributors to public health expenditure, in these conditions make direct payments to health care facilities, both public and private. According to the Report on National Health Accounts 2014-20159, the total expenditure of (SDR) in Benin was estimated at 192.7 billion in 2015 against 214.297 billion in 2014.

This SDR, made up of current health expenditure and capital expenditure in the sector, was 188.47 billion in 2013 and 192.88 billion FCFA in 2012. It is thus noted a increase of 13.70% of the SDR from 2013 to 2014 then a decrease of 10.08% from 2014 to 2015. This decrease is due to the reduction in current expenditure provided by the Government and the Technical and financial partners, which respectively increased from 82.068 billion and 44.355 billion in 2014 to 75.703 billion and 36.313 in 201510.

The distribution of current health expenditure by financing scheme shows that the public administration schemes and compulsory contributory schemes for the financing of health (52.81% in 2014 and 47.43% in 2015)11, constitute the first systems of funding through which populations have benefited from health services. Households, despite their relatively low income, come second, with 44.21% in 2014 and 43.94% in 2015, i.e. almost half of national health expenditure 12. (See the table below after).

Breakdown of current health expenditure by financing scheme (HF) in 2014 and 2015

| Health care financing schemes | 2014 | 2015 | ||

| Expenses

(millions of FCFA) |

% | Expenses

(millions of FCFA) |

% | |

| Public administration schemes and schemes mandatory contributory health financing | 91 970 | 52,81 | 85 556 | 47,43 |

| Voluntary private payment schemes for health care health | 4 389 | 2,52 | 222 | 0,12 |

| Direct payment from households | 77 007 | 44,21 | 79 272 | 43,94 |

| Financing schemes from the rest of the world (non- residents) |

800 | 0,46 | 15 350 | 8,51 |

| Total | 174 166 | 100 | 180 401 | 100 |

Source: SEP/DPP/MS Benin, 2014 and 2015.

Examination of the health system financing scheme shows that the State has been financing, since few years, the sector has less than 8% of its general budget against a community threshold of 15% set by the declaration of Abuja in 2000 to which Benin subscribed. This ratio is continuously falling compared to the 1990s. According to the Accounts of the Health, the largest funder remains households whose contribution to total expenditure of health is 43%, 38.3% and 49% respectively in 2013, 2014 and 201513.

These statistics confirm the general trend observed in West Africa where households largely support their care in the event of illness. Indeed, according to a study carried out on behalf of the Health Finance and Governance project Governance, HFG) by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), on fifteen countries, including nine in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Ghana and Nigeria), households in West Africa (…) pay a higher share major part of total health expenditure than households in most countries outside this region. This statistic is based on data collected between 2011 and 2014 14. The study specifies that in the nine West African countries studied, the health expenditure of households range from 35% of total health expenditure for Burkina Faso to 72% for Nigeria, with an average reaching nearly 52%15.

As for health expenditure by governments, it ranges from 9% for Guinea to 40% for Ghana, with an average of nearly 25%, taking into account a percentage 21% for Nigeria representing both government, NGO and community employers.

This information is further detailed in the “Atlas of Health Statistics of the African Region 2016” from the WHO, which provides country-by-country figures, which confirm the percentage of less than 50% on average of the public in national health expenditure, both for West Africa and for the rest of the continent.

It emerges from the analysis of the expenditure of financing structures in West Africa in general and in Benin in particular that the public administration and donors are the main financing agents of health expenditure, immediately followed by households. It should also be noted that the contribution of households in Benin continues to climb since 2012 (42.22% in 2012, 42.31% in 2013, 44.21% in 2014 and 43.94% in 2015.

This gradual increase in the rate of financing of health expenditure borne by households with already limited resources, confirms the inadequacy of the insurance mechanism disease and pooling for risk sharing. It also poses a problem fairness and equality of citizens before the public health service. Indeed, this part importance of households in public health expenditure actually hides disparities (between affluent people and those with modest or poor incomes) in the care healthcare and a high risk of bidding in pricing for outpatient services

and city medicine, which is increasingly developing in Benin. The consequences of this situation can be detrimental to the economy in the event of an epidemic and, in turn, undermine the efforts made in the implementation of health policies, to build a system of healthy, equitable and resilient to all exogenous shocks. It is in this context of insecurity sanitation for the vast majority of the Beninese population, linked to the structural lack of financing, that in 2017 a major reform of social security and protection sickness, carried by the “Insurance for the reinforcement of human capital” program (ARCH).

C- Health financing from 2016: Governance promising and challenging

Health sector financing covers both the resource mobilization strategy and optimal execution of expenditures to achieve national health goals. The authorities in charge of this sector since 2016 are apparently well aware of this. In evidenced by the resources allocated to the health sector in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF)16 which amounted to 70.319 billion in 2020 against 63.610 billion in 2019, including including unallocated expenses. They are thus up by 6.709 billion, i.e. 9.54% against 9.24% on average for the countries of sub-Saharan Africa17.

This upward trend in the health sector budget corresponds to the overall vision of the country included in its national health policy 2018-2030, worded as follows: “By the year 2030, Benin has an efficient health system based on public initiatives and private, individual and collective, for the permanent offer and availability of health care quality healthcare, fair and accessible to populations of all categories, based on the values of solidarity and risk sharing to meet all healthcare needs of the people of Benin”.

Resolutely subscribing to this vision, the current health authorities have since mobilized the advent of the government of Patrice Talon in 2016, adequate resources to put the foundations of sufficient and sustainable funding to serve the health system resolutely focused on the protection of people. A review of the financial situation of the Health sector18 shows that significant resources continue, despite the multiplicity of challenges of all other sectors, to be injected into health, as shown in the table below.

Budget allocation to the health sector, from 2016 to 2021

| HEADINGS | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Forecasts | Forecasts | Forecasts | Forecasts | Forecasts | Forecasts | |

| 1. HEALTH SECTOR | 85 604 446 011 | 94 735 423 541 | 79 260 498 368 | 75 961 612 009 | 123 242 246 600 | 131 618 422 000 |

| 1.1. Budget Ministry of Health | 69 582 567 000 | 81 065 631 000 | 68 877 166 000 | 63 609 804 000 | 109 471 820 000 | 91 862 422 000 |

| 1.2.Medical evacuations and Health Insurance |

14 215 379 011 | 11 763 204 896 | 5 900 000 400 | 5 804 000 000 | 6 200 560 000 | 7 000 000 000 |

| 1.3. Army and military hospitals police and other health expenses financed by global appropriations |

1 806 500 000 | 1 906 587 645 | 4 483 331 968 | 6 547 808 009 | 7 569 866 600 | 32 756 000 000 |

| 2. GENERAL BUDGET | 1 026 636 634 00 | 1 569 441 660 000 | 1 299 066 000 000 | 1 264 289 000 000 | 1 592 988 999 000 | 1 665 269 130 000 |

| RATIO (1/2) | 8,34% | 6,04% | 6,10% | 6,01% | 7,74% | 7,90% |

| NB:

Direct allocations to the Ministry of Health in 2020 integrate resources with the management of Covid-19 (with the elaboration of the budget summary that took place in the last quarter) |

||||||

Source: Directorate General for the Budget, December 2021.

The analysis of this table reflects that the different budgetary envelopes allocated to the sector of health confirm the desire for overall control of public finances from now on framed by a system of rational governance of State resources.

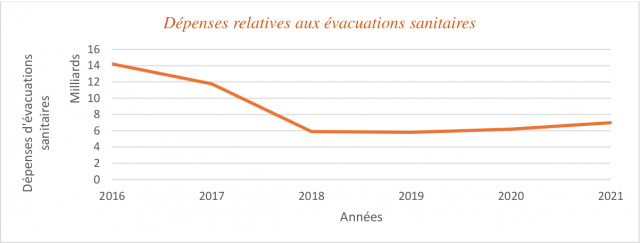

In fact, public health expenditure has evolved almost in sawtooth fashion, taking into account both equity between the beneficiary citizens and the desire to put a definitive end to the sprinkling and waste. This sawtooth evolution noted from the envelope of the year 2016, in the amount of 85,604,446,011 FCFA, to that of 2019 stopped at 75,961,612,009 FCFA, testifies to the government’s desire to make a major strategic choice, that of thoroughly reconsider the envelope of medical evacuations. These evacuations indeed cost each year, before 2016, tens of billions of francs to the State. Beninese, despite the relatively insignificant number of beneficiaries compared to millions other citizens who would die, for lack of the minimum for their medical care adequate in national health facilities. Thus, for 2017, medical evacuations were budgeted for an amount of 11,763,204,896 F against 14,215,379,011 in 2016, i.e. a decrease of 8.27%. In the following years, 2018, 2019, according to the graph below below (on medical evacuations), the amounts allocated have practically dropped, from from 11,763,204,896 F in 2017 to 5,804,000,000 FCFA in 2019, i.e. a drastic reduction of 49.34%. In 2020 and 2021, a slight increase is granted for the payment of services linked to the contractualisation abroad, of the management of the said evacuations19.

Figure VI: Financial evolution of medical evacuations from 2016 to 2021, source: General Directorate of the Budget, December 2021.

This decrease in medical evacuations has had a significant impact on resources overall budgets allocated to the health sector, which are concomitantly experiencing substantial reductions from 2017 to 2019. But from 2019, a financial boom remade in this sector due to the many measures taken by the government for the management epidemiological, economic and especially social of the COVID 19 pandemic. This is how the table displays, for 2020 and 2021, respectively the amounts of 123,242,246,600F and 131,618,422,000 FCFA, significantly higher compared to previous years.

However, it should be noted that despite these measures to reduce expenditure related to evacuations, these are not however suppressed in Benin. A new mode of management is put in place, consisting of contracting with competent private structures national and foreign20, for the management of certain serious pathologies for which Benin does not yet have adequate technical platforms. In parallel, a great deal of effort is being made to ensure that certain establishments are adequately equipped public: as attested by the Beninese Minister of Health in an interview granted on 24 April 2021 (see box no. below), state-of-the-art equipment for the management of same conditions on the national territory21. This explains the steep increase of item 1.3 of the table, army and police hospitals and other health expenditure financed from global appropriations. Expenditure on this item shows, in 2021, the trifle of 32,756,000,000 FCFA against 1,806,500,000 FCFA in 2016, i.e. a unprecedented increase of 181.32%. This increase is the peak of a linear evolution and sustained, observed since 2017.

Box I: Intervention of the Minister of Health regarding medical evacuations

“We are certainly in the future, but there are a lot of achievements. We have established many things. We are no longer evacuating today because we have acquired devices that allow you to no longer evacuate. In a while, the MRI will be finished. Patients who were evacuated just to do an MRI check will no longer leave and very soon with the reference hospital it will be even better. Already, in relation to the evacuations toilets, we have implemented a reform to clean up what was going on as well as possible. In relation to this, it must be said that the cost of evacuations on the State budget was enormous and they are not especially controlled. Today we set up a system which makes it possible to effectively select the patients who really need medical evacuation”.

Source: Benjamin HOUNKPATIN, Minister of Health, interview of April 24, 2020.www.gouv.bj

All in all, this strategic choice of public health financing made under the government of President Patrice Talon calls for three main points of attention:

1. The new public financing strategy is essentially based on rationality public health spending. This now aims to avoid waste of resources and above all the misappropriation of public health expenditure;

2. It also aims for equity, a fundamental criterion of a health strategy geared towards protection of people. Indeed, by drastically reducing the exorbitant expenses medical evacuations reserved for a few hundred privileged people, civil servants or other political personalities, the health authorities are resolutely opting for equitable health expenditure, centered on the equality of all in the use of state resources. This constitutes the philosophy that underpins, among other things, the implementation place and generalization of insurance to strengthen human capital, new mechanism including compulsory health insurance for all. Note that in this context, the State opts for the full coverage of health expenses of the poor and extreme poor of the populations, throughout the territory national.

Box II: New methods of managing medical evacuations

“Thanks to the reforms carried out and the involvement of the Official Travel Unit, the point of the amounts committed increased from fifteen billion one hundred thirty-eight million four one hundred and sixty thousand four hundred and forty-five (15,138,460,445) FCFA for the single year 2015, of which nine billion one hundred ninety-three million two hundred seventy-four one thousand nine hundred and fifty-eight (9,193,274,958) FCFA for transport costs, at five billion eighty-four million (5,084,000,000) FCFA for the period 2018-2020, costs of transportation included.“

Source: Benjamin HOUNKPATIN, Minister of Health, during a press briefing on news methods for managing medical evacuations, Wednesday, September 30, 2020, www.gouv.bj

3. The new financing strategy also aims to modernize the plateau technique at the level of public health establishments, through not only the state-of-the-art equipment of certain hospitals such as the National Hospital Center University Hubert Koutoukou Maga, Mother and Child Hospital, Hospital of instruction of the armies etc. In the same vein, an international reference hospital is under construction in Abomey-Calavi, the objective of which is to offer national and foreign users quality care in all areas, medical and surgical.

However, this financial upturn in the health sector should not overshadow another challenge major strategy. That of covering the entire national territory with adequate human resources and quality. Efforts are certainly underway to find a lasting solution to this problem. protection of persons22. But the other challenge is to reach the convergence threshold, community adopted by the Abuja Agreement, which consists in allocating to the health sector each ECOWAS member country, a share of at least 15% of the national budget. Notwithstanding the financial efforts made in recent years and cited above, Benin is still below this threshold. Indeed, given the point of budgetary allocations to the health sector from 2016 to 2021, the health budget/general budget ratio has remained practically stable since 2017. In 2021, it posted 7.90%, compared to 8.34% in 2016. This finding also emerged in the budget note of the NGO Social Watch Benin for the year 201923 in these terms: “Despite significant health challenges over the past five years, the share of of the budget allocated to the health sector has been declining since 2016; which does not respect the agreement of Abuja (at least 15% of the budget allocated to the health sector) nor the recommendations of WHO (at least 60 US dollars of health expenditure per capita while this expenditure is US$11 in 2019), ranking Benin among the countries that fund health the least24”.

And yet, the achievement of these different thresholds falling under international commitments, in the national budget, although relatively difficult from a macroeconomic point of view, will, certainly, to face the other outstanding charges. These include in particular continue the construction of new local health centers, to provide more modern sanitary equipment to the said centers and to train health professionals experienced in sufficient numbers, for universal and truly equitable coverage of populations, both in prevention, in promotion, and in quality health care.

The Government of Benin has opted for universal health coverage by setting up the Insurance program for the reinforcement of human capital (ARCH). The insurance- illness is thus made compulsory for all residents on the national territory under the terms of article 17 of law n ° 2020 – 37 of February 03, 2021 on the protection of the health of people in the Republic of Benin. This obligation systematically becomes a legal debt for all employers, public and private, who must now subscribe to health insurance to all their employees, as provided for in article 18 of the law. During this time, the State takes steps to cover the health expenses of people poor and extreme poor living in the national territory.

At a time when the Government of Benin has been mobilizing, since 2016, significant resources to deal with the many multi-sectoral structural reforms and the construction of modern infrastructure for sustainable development, this commitment in people’s health sounds like a major challenge. On this subject, thoughts from must be carried out at the highest level in order to find supporting mechanisms or nets for adequate and sustainable financing of the costs induced by the operationalization of this commitment of the State in favor of its many beneficiaries and the poor and poor extremes of the nation. Because, it is obvious that the only net of the national budget for bearing the large expenses of universal health insurance might seem unsustainable for the country and, ultimately, hamper the achievement of equitable protection objectives targeted by the government. On this subject, there are avenues for reflection.

In fact, today in the world there are two mechanisms for financing expenditure public health services: national health systems favor the tax mechanism while that health insurance systems have long favored the mechanism based on social contributions. In this regard, Bruno Palier states: “At the origin of health systems, it seemed logical to finance health insurance expenditure through social security contributions deducted from wages, since the first objective was to guarantee an income of replacement for the sick. Today, insofar as health systems do not limit plus their coverage to those who work (and therefore contribute), and where health expenditure mainly finance health care (unrelated to work income), it seems more appropriate to finance expenditure through taxation” 25. Taking into account this assertion of Bruno Palier, it is recommended that the Government of Benin direct the search for sustainable financing of this new health policy in the direction of the pooling of different nets that exist today, including:

✓ The participation of public and private employers as already established in the law aforementioned;

✓ The contribution in the form of co-payments from the insured themselves in order to anticipate and to prevent abuses linked to possible moral hazards, and above all to hold these beneficiaries of the insurance in the consumption of care and other health services;

✓ The creation, if possible, of some tax levies on products such as tobacco, alcohol and other luxury products, the sum of which will be allocated to the envelope dedicated to the financing of health insurance;

✓ The medium-term decentralization of the health insurance management system in order to to include municipalities in the planning, management and evaluation of this policy health. This would make flow management and close monitoring and personalized beneficiaries through local contracts signed between the authorities on the one hand, and approved health facilities and insurance companies private, on the other hand.

All in all, Benin has been writing, since 2016, a new page in its policy of health financing after decades of wandering and sprinkling huge resources without relevant results. The construction of new hospital infrastructures, the renovation and modernization of old ones and the vast program of equipping state-of-the-art national and departmental hospitals, mobilize financial resources exorbitant thanks to the political will of the government in place. To these structural advances added to the initiation and institutionalization of universal health insurance by law No. 2020-37 of February 3, 2020 on the protection of human health in the Republic of Benin, one of the four components of the Insurance program for the strengthening of human capital (ARCH). This unprecedented program in the health history of the country, revolutionizes the mechanism of covered by compulsory health insurance for all residents of the national territory. But its financing poses enormous challenges, the recovery of which will result from the strategy put in place. in place, which will have to go through the participation of all the actors, in this case the political decision-makers, experts, actors in the field and technical and financial partners.

1 MATHONNAT, J., Biology Reports, volume 331, December 2008, Paris, pages 942-951.

2 LANDING, Bruno, The Reform of health systems, ed University Press of France, Collection: What do I know? February 2017, p 25.

3 Benin has just moved from low-income to lower-middle-income country status, according to the new classification from the World Bank, updated each year on July 1 and based on gross national income (GNI) per capita for 2019. Thus, Benin went from a GNI per capita of $870 in 2018 to $1250 in 2019, which explains this requalification, the World Bank underlining however, that the revision of the national accounts played an important role in the upward updating. See Benin – Politics & Legal, 06 July 2020 – pp.16-24, by COMMODAFRICA.

4 The Bamako Initiative (BI) (1987 in Mali) aimed to improve access to primary health care by improving quality. She was leaning on the search for financial viability and equity of health services. Therefore, health facilities should offer a package minimum activities to meet the basic health needs of the communities. Access to medicines and participation community were fundamental principles. Thus, health facilities should have generic essential drugs to address essential health issues. Co-financing and co-management of health care and services should allow to ensure the sustainability of services and more transparency. The Bamako Initiative also advocated the participation of communities in the health decision making. Health committees whose members are elected in their villages are created. This committee elects in s. we breast the management Committee. It has made it possible to set up supply circuits for essential drugs, to resolve or reduce drug shortages. On the other hand, the exclusion of the poor or destitute from access to care is one of the major criticisms.

5 National Community Health Policy, Ministry of Health, 2015, pp11-12. See also Rapid Health System Assessment of Benin, April 2006, pp.21-23.

6 National Community Health Policy, op-cit.

7 The goal of universal health coverage is to ensure that all people have access to health services without incur financial difficulties. Each year, approximately one hundred (100) million people fall into poverty for having financed their pockets of health services and one hundred and fifty (150) million are exposed to financial disaster for the same cause. Protection against financial risk is at the heart of universal health coverage. This is also the central objective of health financing policy. WHO, December 2014. The method of financing determines the availability and affordability of health services. As asserted MATHONNAT, J., 2008, above. Having sufficient funds for health today is a fundamental issue, particularly in Africa. This issue of health financing is not only a concern for social equity, but also an issue major policy. The World Health Organization notes that “In many countries, health spending remains below the threshold defined critical for the provision of a range of basic health services. For rich countries, the challenge is that health spending are not increasing despite the aging of the population (which has consequences for revenues and expenditures) and the increase in costs due to technological progress (a challenge that some poorer countries also face)” ( see more details in Box 1 below). The mode of health financing in a country is fundamentally dependent on the health system of this country.

8 National Community Health Policy, op-cit.

9 Report on national health accounts (CNS) 2014-2015, published in August 2017, Ministry of Health. This document is established by way of restitution, for each year, on the evolution of health financing agents, the resources mobilized as well as the various trends in funding needs related mainly to malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

10 Report on national health accounts 2014-2015, op-cit. In our investigations at the Department of Programming and Foresight of the Ministry of Health, no other national health account has been carried out since this last account of 2014-2015.

11 Report on national health accounts 2014-2015, op-cit;

12 Report on national health accounts 2014-2015, op-cit;

13 National Health Development Plan 2018-2022, p54.

14 Report of a study entitled “The financing of universal health coverage and family planning: Multiregional panoramic study and analysis of certain West African countries, USAID, January 2017.

15 Report on national health accounts 2014-2015, op-cit. In our investigations at the Programming and Forecasting Department of the Ministry of Health, no other national health account has been carried out since this last account of 2014-2015.

16 Medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF) of the Ministry of Health, Directorate of Programming and Forecasting, 2019.

17 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) Ministry of Health, 2020.

18 The compilation of annual budget financing, the subject of the table, comes verbatim from the Directorate General of the Budget in December 2021.

19 As part of the implementation of the Government Action Program 2016-2021, the Ministry of Health signed a contract for service with the Paris Hospital Foundation (PHF) group on January 9, 2018 for the controlled management of external medical evacuations. After more than two (02) years of implementation, the internal review carried out by the Ministry of Health reveals an overall execution satisfaction of the terms of the contract by both parties. It notes that, over the implementation period, for an amount of 5,084,000,000 FCFA paid to PHF, 322 patients were taken care of, i.e. an average cost, including logistics, of 15,788,820 CFA francs per patient evacuated in France. When only care (inpatient and outpatient) is taken into account, the average cost of care for a patient is at CFAF 11,525,839. The expenditure items are care (70%), logistics (27%) and miscellaneous costs (03%). The three hospitals of the group PHF received 90% of resources and patients, with the rest covered by non-PHF hospitals. Conditions frequently covered by medical evacuation are cardiovascular diseases and cancers, the treatment of which is very expensive for Benin. Source : Ministry of Health, September 2020.

20 In June 2019, the Beninese Minister of Health, Benjamin Hounkpatin and his Ivorian counterpart, Eugène Aka Aouélé signed, in Abidjan, a partnership agreement between Benin and the Alassane Ouattara National Center for Medical Oncology and Radiotherapy in Cocody. This agreement partnership which is part of the strengthening of bilateral cooperation between the two countries, will allow the management radiotherapy of people with cancer in Benin in the Alassane Ouattara National Center for Medical Oncology and Radiotherapy. Source: Ministry of Health communication unit; www.gouv.bj.

21 In order to allow the Hubert Koutoukou MAGA National University Hospital Center of Cotonou to carry out certain specific examinations, linked to the heart in this case, the government of Benin decided, during its Council of Ministers of December 8, 2021, (see Account report n°37 of the Council of Ministers dated December 8, 2021), the acquisition and installation of a 64-slice/128-slice scanner with cardio option. This same Reference Center has had, since November 26, 2020, a magnetic resonance imaging device (IRM), again by decision of the Beninese government.

22 In an article published by GBAGUIDI Ariel in the daily La Nation on June 18, 2021, we read: “After the 1600 agents recruited for the benefit of the Ministry of Health, a second wave is still expected within a few months. The objective is to strengthen the resources human resources in the health sector. Anything to make up for the lack of personnel noted in several health structures in the country. “The government will again launch another recruitment of 1,400 health workers within two years in order to reach the number of 3,000 announced agents. Today, we have an imbalance in terms of distribution, “said Minister of Health Benjamin HOUNKPATIN, Saturday May 15, after the launch of the recruitment competition for 1600 agents. Ministerial authority explains that cities are much busier than rural areas. What the Beninese Executive is working to correct”.

23 Social Watch Benin, Health Sector Budget Note, World Bank, 2019.

24 Social Watch Benin, Health Sector Budget Note, World Bank, 2019.

25 PALIER, Bruno, The reform of health systems, February 2017, pp 25-26.

Bibliographic references

MATHONNAT, J., Biology Reports, volume 331, December 2008, Paris;

PALIER, Bruno, The Reform of health systems, ed University Press of France, Collection: What do I know? February 2017;

Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF), Ministry of Health, Directorate of Programming and Forecasting, 2019;

Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF,) Ministry of Health, 2020;

Law No. 2020-37 of February 3, 2020 on the protection of human health in the Republic of Benin;

Budget note on the health sector, Social Watch Benin, World Bank, 2019;

National Health Development Plan 2018-2022, Benin;

National Community Health Policy, Ministry of Health, 2015, pp11-12. See also Benin Rapid Health System Assessment, April 2006;

Politics and Legal, July 06, 2020 – COMMODAFRICA;

Report on Financing Universal Health Coverage and Family Planning: Multiregional Panoramic Study and Analysis of Selected West African Countries, USAID, January 2017;

Report on national health accounts (CNS) 2014-2015, published in August 2017, Ministry of Health.